How Real is Intersubjectivity?

This post is a continuation of an earlier one “Intersubjectivity as Mutually Understood Subjectivity“.

If the intersubjective mode of understanding includes experiences that multiple people can talk about and use social verification methods to refine their mutual understanding, then one might wonder whether intersubjectivity is nothing more than agreed upon myths and other things that can be called our “collective imaginary”. That is part of it, but it would be false to assume that anything objective is real and anything intersubjective has no basis in ground reality.

Notably, the dichotomy between objectivity and intersubjectivity relates to the distinction between so-called primary and secondary qualities. This was most explicitly articulated by John Locke in his Essay concerning Human Understanding, but earlier thinkers such as Galileo and Descartes made similar distinctions. Primary qualities are thought to be properties of objects that are independent of any observer, such as solidity, extension, motion, number, and figure. Secondary qualities are thought to be properties that partially rely on sensations within observers, such as color, taste, smell, and sound. They can be described as the effect things have on certain people. Knowledge that comes from secondary qualities does not provide objective facts about things. Primary qualities are measurable aspects of physical reality. Secondary qualities are subjective but can become intersubjective, such as when people discuss colors and come to a mutual understanding of this phenomenon. Both primary and secondary qualities can be studied and measured objectively in certain ways, but in the case of secondary qualities this often relies on advanced neurological scanning devices. We know that while humans usually perceive 3 primary colors, these do not exist objectively. Each of these merely corresponds to a spectrum of light. It is possible to correlate a range of wavelengths to the neurological patterns in the brain when someone observes this wavelength, but this is not the same thing as the firsthand experience of seeing color. When people discuss colors, they are forming intersubjective understandings of their experiences.

For more clarity on this distinction, consider the following thought experiment: suppose a scientist enters a recently discovered underground cave that nobody else has ever seen. While in the cave this scientist communicates his observations via radio to his fellow scientists on the surface. In this situation, the scientist’s reports to the others drives the social verification and it is possible that these reports can be considered objective knowledge even to those on the surface, but only if there is already an objective understanding of the kinds of things that the one in the cave is reporting on. If, for example, he says “I see various rock formations, some of which seem to have quartz and some of which seem to have shiny metals” then this account can be easily understood by those on the surface because they can evaluate his claims based on their understanding and previous observations of similar caves (and also use the criteria for justifying claims outlined in a previous post).

Anyone who has ever been in a cave with someone else or who has seen pictures or video of a cave in the presence of others probably has an objective understanding of the typical features of caves. Such people can talk about caves with each other and can easily have a mutual understanding of what a cave is and what kinds of things one can expect to find in them. Imagine, though, as a counterexample that there are certain caves that can be found in many places but where only one person can go inside at a time. Anyone who goes into the cave sees and hears unique things that they do not see or hear anywhere else. Imagine that most people have had experiences of going into these special caves by themselves (and never with anyone else) and that no cave of this kind has ever been documented visually or auditorily. In this case it would be very difficult for someone to talk about this kind of cave with anyone else. Although it would be difficult for people to explain their experiences of exploring these caves to others, the fact that others have had similar experiences makes mutual understanding possible. People would find ways of communicating and from this they should be able to get a pretty good idea that others have had cave experiences similar to their own. In this situation, there is no objective understanding of what these caves look like or sound like, but people can nonetheless work towards a certain degree of mutual understanding of these phenomena and this can be considered intersubjective.

To take another example, let’s say that several people each have a crazy dream that is unlike anything they have ever experienced in their lives and that each person’s dreams are remarkably similar. Consider the possibility that several people could have similar dreams and that each involve seeing objects and hearing sounds that are quite unlike anything else that one can ever see or hear in their waking life. If these people were to be in the same room the day after having these dreams and were then to try to explain their dreams to each other, how much mutual understanding might be possible? It would likely be quite difficult for them to explain their dreams to each other and to get an idea of the other people’s dreams, but eventually they would probably be able to use language to symbolically communicate with each other the details of their dreams and from this they would be able to socially verify that they each had similar crazy dreams. These people would then have intersubjective knowledge of these dreams.

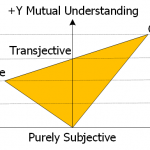

It is usually easier to develop mutual understanding for the objective than for the intersubjective. It is important to note that the most significant criterion that determines whether a certain point of common understanding is objective or intersubjective is how this phenomenon would become socially verified. If the phenomenon in question is both observed and socially verified within a communications medium, we can call it intra-medium. If it cannot be observed within any medium, it can be called extra-medium. In the latter case, everyone would still have to use a medium to communicate anything about the phenomenon and any social verification would have to rely on that, but the means of observation for each person would be separate from the medium they would use for any communication about this phenomenon.

Since we rely on communications media for all mutual understanding, intra-medium social verification is a more direct process. There is a variety of ways that one can communicate through a medium while simultaneously giving indication of things observed through this medium. There is a variety of communicative tactics that one can employ to indicate the quality and quantity of things, including interacting with something, grasping it, moving around it, making facial features, gesturing with one’s hands, and speaking with tonal inflections to convey nuances. When things can be seen and heard among multiple conscious beings while they also use these sorts of tactics to convey to each other that they are having these perceptions, this can serve as social verification and can build higher levels of mutual understanding.

The extra-medium social verification process is indirect and relies on analogies and correlations to phenomena that cannot be seen nor heard. This would include senses that are not connected to a communicative medium, including touch, smell, and taste. For these, we can build mutual understanding by perceiving them ourselves and then making correlative judgments to other phenomena that occur within the auditory and visual media. For example, one can smell something awful and make a certain facial grimace and then later see someone from a distance making a similar facial expression and conclude that person likely smelled something awful as well. We could similarly develop mutual understanding of any felt emotions and also other types of inner experiences are not connected to any medium. For those, we would still have to use a medium as a means of communicating any details about such experiences. This might be possible by noticing the patterns of correlations of felt inner experiences and your own behaviors and then noticing other beings behaving similarly. This would indicate to you that they are having similar inner experiences. For example, you might feel happy and then you smile and speak in a higher intonation and you see and hear someone else doing the same thing, which would then indicate that they are happy.

However, it is inevitable that in most cases you would be less certain of the mutual understanding of someone else’s inner experiences than you are of things that can be directly seen and heard. For this reason, the intra-medium social verification process has the potential to lead to an overall higher degree of mutual understanding than the extra-medium. This means that we can develop detailed mutual understanding of objective things quite a lot easier than we can anything that is intersubjective. This should not be taken to entail, however, that intersubjective things are necessarily always imaginary and invented human constructions.

In general, things that are objective are those which are external to consciousness such that their existence does not depend on anyone’s belief in it. For example, the chemical and molecular realities of the rocks and minerals and plant and animal life in the world do not owe their existence to any conscious person’s belief. When someone has a particular belief about something imaginary then this is subjective. In another one of Harari’s books called Sapiens, he sought to understand the factors that led homo sapiens to develop complex societies and he argued that one vital element is having masses of people with similar legends, myths, and beliefs about the social structure in which they live. He recognized that these are all examples of intersubjectivity because they are beliefs that are shared throughout a community and their continued existence does not depend on any specific person believing them. These beliefs inevitably evolve, but they can stay rather constant throughout a person’s lifetime, as determined by common beliefs of the people of the society in which one lives. Harari pointed out that these beliefs can include, for example, the notion that people are naturally organized into hierarchical castes, as the ancient Babylonians believed, or that people are naturally equal and naturally have human rights, as a significant percent of people in the world today tend to believe. He argued that these two examples are equally fictitious because they have no basis in objective reality, but he assumes that any belief that does not have a basis in physical/material reality must necessarily be fictional.

The flaw in Harari’s reasoning is that he does not realize that the objective/intersubjective distinction is largely differentiated by how one comes to believe things and is not necessarily based on whether the topic of our mutual understanding is real or imaginary. If there is any aspect of consciousness that could potentially be shared among a community of individuals but that can only be understood from first person experience (members of the community having similar conscious experiences) then such beliefs would be intersubjective. These areas of mutual understanding could be shared among a community and they certainly would not be objective since their existence would depend on the experience of a conscious being. Their existence, however, would not depend on anyone’s belief in them. The value of money depends on people’s belief in it, and thus we can say that money’s existence depends on this belief, but there might be aspects of our inner worlds that can be mutually understood and that would exist just the same even if they were not mutually understood. The essential aspects of consciousness, if there are any, could conceivably be true whether or not any conscious person chooses to acknowledge their existence.

Harari argues that human rights have no more basis in reality than myths that were invented by humans and that have been propagated across many people within a certain culture. But if it is actually conceivable that human rights might have some sort of a basis in fact because it might be the case that they were ultimately derived from certain essential aspects of lived conscious experience that would be universal to all humans. For example, consider both a rock and a building. The rock existed before any humans came onto the scene. The building was planned, designed, and built by humans. These can both be measured and studied and understood objectively. The intersubjective realm similarly includes things that were invented by people (like the building was) and this mode of understanding might also include things that existed before anyone thought about them or talked about them. Money, governments, legal systems, fictional stories, and cultural norms were conceived of and invented by people. It our shared values are intersubjective and there might possibly be some shared core values that are a part of base reality.

We don’t want to presume this to be the case, since at this point, we don’t even have the epistemological tools to make such a judgment. This is, however, conceivable, and it is conceivable that this could be the case even if nobody believed in human rights. These could be things that were discovered by mankind in recent centuries in a way somewhat similar to how electromagnetism was discovered over a century ago and how some people now understand this fact about reality but not everybody does. Centuries ago, when nobody believed in electromagnetism, that did not have any bearing on this fundamental force’s factual existence.